Week 43 - 2025

This week was a huge W in terms of productivity and family time.

The week started off with deepawali celebrations. Lots of great family photos after a long time. Also I got to write a blog this week on the day of deepawali. It is on garbage collection in Go. Check it out here.

The highlight of the week was the visit to Raja Thoppu Dam. Fortunately, it was a cloudy day with a bit of drizzles and cool breezes.

I got to cover a good amount of Mastering Go this week. Here are the stuff that I learnt over the week.

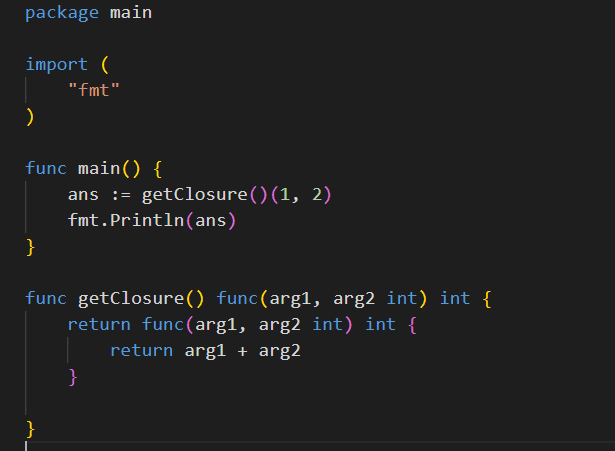

Closures in Go

Functions are treated as first class citizens in Golang. What this means is you can treat functions as any other data type. But mostly it means that you can pass functions as arguments to another function. Take a look at the below screenshot of how the function is returned from another function.

Function named returns

Go allows naming the return variables. This allows the function to assign variables during its flow and having a naked return statement. Although having a naked return statement doesn’t help readability much. The code below serves as an example

package main

import "fmt"

func IsEven(input int) (output bool) {

if input%2 == 0 {

output = true

} else {

output = false

}

return

}

func main() {

fmt.Println(IsEven(5))

}

Defining struct type on bound methods

When you define a method on struct you have two options. You can bind it to the struct like so func (s struct) method() or bind it to the pointer of the struct like so func (s *struct) method(). The difference between both is that when you bind it on the pointer of the struct, obviously the pointer is passed to the function and any changes done inside method would result in changing the underlying struct. This way doesn’t take up any extra memory.

Now when you bind it to the struct itself, the struct is copied into new memory address and then the copied value is passed to the function. Since a copy is passed, any changes to the struct wouldn’t cause changes to the underlying struct. As the size of the struct increases, the memory taken up will also increase. So the dev needs to be vary of this fact

Buffered and unbuffered reads

Take a look at this piece of code

func readUnbuffered() error {

file, err := os.Open(testFileName)

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("failed to open file for unbuffered read: %w", err)

}

buffer := make([]byte, 1) // Read buffer size is 1 byte

bytesRead := 0

for {

n, err := file.Read(buffer)

if n == 0 || err == io.EOF {

break

}

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("unbuffered read error: %w", err)

}

bytesRead += n

}

return nil

}

This is an example of unbuffered read. Since the byte slice provided to os.File.Read method is of size 1 byte, the number of read syscalls made would be equal to the size of file being read.

The flipside to this is buffered read.

func readBuffered() error {

file, err := os.Open(testFileName)

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("failed to open file for buffered read: %w", err)

}

defer file.Close()

reader := bufio.NewReader(file)

bytesRead := 0

for {

_, err := reader.ReadByte()

if err == io.EOF {

break

}

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("buffered read error: %w", err)

}

bytesRead++

}

return nil

}

Here the bufio.NewReader fills up the internal buffer (usually 4kb - although could be defined with bufio.NewReaderSize) before making another syscall.

Now you could argue, well I could do os.File.Read with a fairly large buffer. Context matters. If you want to process the whole file, you could create a buffer of the file size to make exactly one syscall and avoid the overhead of the bufio package.

But if you want a chunked processing of the file, bufio would be a better bet as it handles buffer management.

That is it for the week, in the upcoming week, I’m looking forward to build out a video chunking and transcoding app.

Thank you very much for reading if you have made it this far 💛.